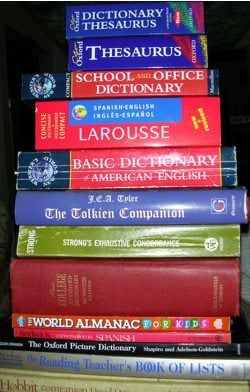

Since then I’ve taught many students who seek to improve their writing by using “better” words. Their revision strategies focus on replacing plain words with big, shiny ones. Such students usually rely on a thesaurus, now more available to a writer than ever before as a tool in many word-processing programs. But dressing up a piece of prose with thesaurus-words tends not to work well. And here’s why: a thesaurus suggests words without explaining nuances of meaning and levels of diction. So if you choose substitute-words from a thesaurus, it’s likely that your writing will look as though you’ve done just that. The thesaurus-words are likely to look odd and awkward, or as a writer relying on Microsoft Word’s thesaurus might put it, “extraordinary and uncoordinated.” When I see that sort of strange diction in a student’s writing and ask whether a thesaurus is involved, the answer, always, is yes. A thesaurus might be a helpful tool to jog a writer’s memory by calling up a familiar word that’s just out of reach. But to expand the possibilities of a writer’s vocabulary, a collegiate dictionary is a much better choice, offering explanations of the differences in meaning and use among closely related words. Here’s just one example: Merriam-Webster’s treatment of synonyms for awkward. What student-writers need to realize is that it’s not ornate vocabulary or word-substitution that makes good writing. Clarity, concision, and organization are far more important in engaging and persuading a reader to find merit in what you’re saying. If you’re tempted to use the thesaurus the next time you’re working on an essay, consider what is about to happen to this sentence: Michael Leddy teaches college English and blogs at Orange Crate Art.